I have been reading Parker Palmer’s The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life (Jossey-Bass, 2007). In the opening chapter Palmer discusses the complexities of being a teacher and how rewarding the role can be as well as how hard it can be also.

One of the things he discusses is how he can at times feel a “transparent sham”1. I feel the two words keenly. As someone who has come to teaching as a second or third career, I do not have the experience of some of my colleagues, in addition to this, I am often younger or around the same age as the students on the UAL short courses that I run. This combined with trying to teach in a less instructional and didactic way can feel challenging and I can start to wonder if my validity is being pondered by students. When this happens, I do feel transparent. It feels as though I am a transparent sham. In these moment, I try to remain open to what students are needing from me (be a it a more instructive way of learning or a boost in confidence etc) and I also try to hold my own truths and beliefs.

Within the ARP project focus of teaching at Sunny Arts, my initial awkwardness at asking students to operate outside of their comfort zones, transferred to the students, this was gone once we had gotten to know one another. Perhaps with new students, the experimental drawings could be introduced in session 3 or 4

Palmer breaks teaching down into these parts:

First, the subjects we teach are as large and complex as life, so our knowledge of them is always flawed and partial. No matter how we devote ourselves to reading and research, teaching requires a command of content that always eludes our grasp. Second, the students we teach are larger than life and even more complex. To see them clearly and see them whole, and respond to them wisely in the moment, requires a fusion of Freud and Solomon that few of us achieve. 2

Palmer here is saying that teaching is not merely a recital of knowledge or material required to answer exam questions, it is instead a transaction between people that it requires wisdom and insight into others as well as ourselves:

But there is another reason for these complexities: we teach who we are. Teaching, like any truly human activity, emerges from one’s inwardness, for better or worse. As I teach, I project the condition of my soul onto my students, my subject, and our way of being together. The entanglements I experience in the classroom are often no more or less than the convolutions of my inner life. Viewed from this angle, teaching holds a mirror to the soul. If I am willing to look in that mirror, and not run from what I see, I have a chance to gain self-knowledge—and knowing myself is as crucial to good teaching as knowing my students and my subject. 3

I believe this to be true. I would perhaps say it in different terms, I would say that I feel being grounded in one’s self makes a difference to how we communicate. I know that when I feel grounded, I communicate in a way that is more confident and therefore clearer and easier to access for students. I think this is crucial when asking students to step outside of their comfort zone. In the evening drop in classes I teach at City Academy, I am often working with new students who do not made work regularly. Asking them to try experimental things or be less concerned with the representational outcome of a work can feel like a risk to them. It can feel exposing. I believe in these situations it is important for the student that my belief in what I am asking is steadfast. I believe it allows them to be held in this moment when they feel they are in an unknown place.

Palmer attributes the ability to know students with self-knowledge:

In fact, knowing my students and my subject depends heavily on self-knowledge. When I do not know myself, I cannot know who my students are. I will see them through a glass darkly, in the shadows of my unexamined life—and when I cannot see them clearly I cannot teach them well. When I do not know myself, I cannot know my subject—not at the deepest levels of embodied, personal meaning. I will know it only abstractly, from a distance, a congeries of concepts as far removed from the world as I am from personal truth. 4

The term embodied is one that interests me as this is one of things I am concerned with in both my teaching practice, in my work as an artist, in my life in general and it is one of the things I most want my students to be able to access. To know one self, is something that gives us access to our own truth, when we speak our truth it can allow others to connect with us. When we can access an embodied way of being, we can make work that speaks our truth. When our work speaks our truth it has the greatest chance of connecting with other people. I think one of the fundamental human needs is connection.

In the following chapter Teaching Beyond Technique, Palmer says:

The techniques I have mastered do not disappear, but neither do they suffice. Face to face with my students, only one resource is at my immediate command: my identity, my selfhood, my sense of this “I” who teaches—without which I have no sense of the “Thou” who learns. Here is a secret hidden in plain sight: good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher. 5

Fundamentally an engaged teacher, offers up to others a way to journey through life, they offer students a way of being in the world. For me being an artist is a way of journeying through life. An art practice is a container for how we see the world around us and what we wish to say about it. It also holds the values which I use to guide me in my life. Being an artist offers the luxury of a language that we can use to communicate and speak in ways that we are not always able do with words. This is a pretty powerful thing. It is something that I respect and want to share with others.

In every class I teach, my ability to connect with my students, and to connect them with the subject, depends less on the methods I use than on the degree to which I know and trust my selfhood—and am willing to make it available and vulnerable in the service of learning.6

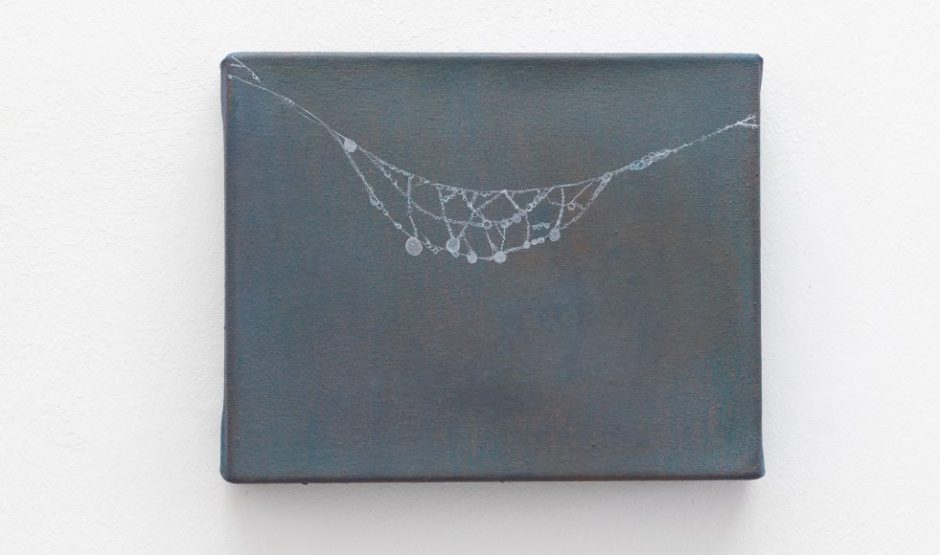

I believe that connection is the key, when I am grounded or connected with myself, I am able to connect to the subject I am teaching, with my students, so that students can learn to weave a world for themselves.

References:

- Patrick Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life, Jossey-Bass, 2007, page 15

- Patrick Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life, Jossey-Bass, 2007, page 30

- Patrick Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life, Jossey-Bass, 2007, page 45

- Patrick Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life, Jossey-Bass, 2007, page 68

- Patrick Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life, Jossey-Bass, 2007, page 97

- Patrick Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life, Jossey-Bass, 2007, page 130